Bridging the Divide Between Text and Image:

Susan G. Scott’s Les enfants terribles

by Rosie Prata*

In its original meaning, to translate means to change the form, meaning or nature of one thing into another. “Ancient writers,” writes John Bordo, “used the word to mark the passage of mortals to the spirit world or give visible form to deathless gods.”[1] Susan G. Scott has taken the warring child-gods of Jean Cocteau’s Les enfants terribles, who exist only as ghosts in the imaginations of the novel’s readers, and endowed upon them a palpable form through the application of paint to canvas. She has translated poetry into image, and thus breathed everlasting life into the bodiless characters. A translation is often given credence according to its level of conformity with its source material, but in this instance, this value is moot. Scott’s paintings may have hatched as ideas inspired by Cocteau’s novel, but now fully formed, they stand apart from their originator and function as entities in their own right. In tracing the progression of the acquired meaning of the works, one finds that the two levels – Cocteau and the story itself, and Scott’s impetus behind creating the paintings – need not interfere with each other in order for the final product, Scott’s paintings, to be understood. This information is however very interesting to consider, and provides different and helpful perspectives. Three readings of the series will be explored: the paintings as they relate to the book and to Cocteau as author, the paintings as they were intended by Scott, and finally, the paintings as paint on canvas, entirely authorless and unclouded by the looming shadows of history and biography.

Jean Cocteau’s 1929 novel, Les Enfants terribles, is a dark and psychologically disturbing delve into the peculiar, near-incestuous relationship between Elisabeth and Paul, a teenaged brother-sister duo based in Paris in the 1930s. The story opens immediately with blood and tragedy, setting the tone for the rest of the book. A fourteen year old Paul, enamoured with his handsome and hyper-masculine older schoolmate Dargelos, engages in a frightening schoolboy battle that ends with his hero hurtling a cataclysmic blow to Paul’s chest with a snowball. This injury, dealt to Paul’s heart, sets in motion the course of the remainder of the novel’s events. Dazed and bleeding, lying on the ground, he is rescued by his friend and admirer, Gerard, a boy who is not charismatic enough to be desired by anyone, but is non-threatening enough to be invited to be a spectator at the theatre of his mythic friends’ lives. Gerard takes Paul home by taxi, where his dying, neglectful mother and possessive sister, Elisabeth, reside. Paul is condemned to an indeterminable amount of bed rest.

Their mother perishes soon after his accident, and the two orphans are left alone in their house, looked after financially by the detached doctor and kept fed by the indifferent and non-interfering housekeeper Mariette. Lapsing into lazy inactivity, Paul gradually cocoons himself in the nest of the bedroom he shares with his sister (called ‘the Room’), along with Gerard, who curls up in a bed of rags and shawls, and later Agathe, a similarly motherless workmate of Elisabeth’s, who moves into their mother’s old bedroom. “This room they shared was as it were a shell in which they lived, washed, dressed together as naturally as if they were twin halves of a single body,”[2] Cocteau explains. The four orphans disengage from the rest of society, absorbing themselves wholly in creating an alternate reality, impenetrable to any outsider. In this obscure and absurd world, Paul and Elisabeth act as the key players, observed by the mesmerised Gerard and Agathe, as they engage in a never-ending Game of their own invention whereby they incessantly taunt and attempt to sabotage the other. “The word ‘Game’”, writes Cocteau, “was by no means accurate, but it was the term Paul had selected to denote that state of semi-consciousness in which children float immersed.”[3]

Dargelos is described as militaristic, athletic, arrogant, and dramatic, dressed as Athalie in the photograph that is made into treasure in the book, cementing his image. The last orphan to join their troupe is the beautiful Agathe, whose features bear an uncanny resemblance to Dargelos’. Her name is mocked for being so similar to agate, which is what marbles are made of. This connection links her even further to Dargelos: his snowball is accused of having a stone inside of it,[4] and is described as a “marble-fisted…marble-hearted blow,”[5] while he himself is the image of a Greek god carved from marble. Paul realises that he loves Agathe, as she is the culmination of all the attributes he has ever loved. The two are stopped from revealing their love to each other by Elisabeth, who becomes consumed with a wild and incestuous jealousy, instead manipulating the situation so that Gerard and Agathe end up married.

Cocteau, a deeply poetic soul who had been touched by tragedy is his own life, wrote the book in the space of a few weeks while recovering from an addiction to opium.[6] Sinister darkness permeates all aspects of the story, most likely as a direct result of the daily discomfort he was experiencing. Cocteau had become addicted to opium after the sudden death of Raymond Radiguet, a young poet and protégé of Cocteau’s who had caught typhoid fever while the two were on holiday. Cocteau had paired up with Radiguet when the boy was just fifteen, and this information is significant when one realises the similar ages of the characters in the book. The author paints a peculiar portrait of childhood as a menacing and mysterious cult. “Their rites are obscure, inexorably secret; calling, we know, for infinite cunning, for ordeal by fear or torture; requiring victims, summary executions, human sacrifices. The particular mysteries are impenetrable; the faithful speak a cryptic tongue; even if we were to chance to overhear unseen, we would be none the wiser.”[7]

Dargelos re-enters Paul’s life a few years later. He gets Gerard to deliver a present to Paul; another ball, but this one not made of snow, but rather black poison: opium. The tragic final scene echoes the first. On the schoolboys’ battlefield, Dargelos’ snowball had “come crashing on his mouth, his jaws are stuffed with snow, his tongue is paralyzed.”[8] In the concluding scene, Paul wilfully ingests the second ball his hero has sent him, and it slowly kills him, making him break out into feverish cold sweats. He is discovered by Agathe and Elisabeth, the truth is revealed about Elisabeth’s misdoings, the sister reaches for a revolver, and the two siblings end their lives in a terrifically manic instant. Peter Read suggests that Cocteau transposes his own situation, being caught “between oedipal loyalty and homosexual attraction”[9] onto Paul, who is similarly afflicted with the taboos of incestuous and homosexual desires. Cocteau’s decision to end Paul’s life with opium was probably a cathartic exercise. He has Paul ingest the opium; it is inside Paul, and Paul is dead, and thus the opium is gone. Cocteau has banished his addiction through his fiction.

Susan G. Scott, smitten like so many others with the dark romance of Cocteau’s poetic tale, endeavoured to represent it pictorially in a series titled “Les Enfants Terribles: A Painter’s Narrative” (2001-2002). “My first rereading of Les Enfants Terribles in over 30 years,” the artist writes in her notebook, reproduced in sketchbook folios presented during the exhibition, “and I am still totally pulled by the magic of the atmosphere of this novel.”[10] Scott is a narrative painter, and describes herself as a storyteller. Her work often deals with psychological issues, which she encourages the viewer to participate in. She hopes that they will discover more than one resolution.[11] Most of her series have been inspired by literature. Often, the stories she chooses to work from are dark, disturbing, and emotionally troubling, with hints at violent subject matter. Her work also often involves children. Series both preceding and following Les Enfant Terribles (Blindman’s Buff, The Dreamer, Yiddish Folk Tales, Fabula and Reveries) use children as the cast of figures. Scott uses models and works from photographs, drawing from images of her own children or the children of friends and neighbours, while using the old masters for inspiration regarding figural composition and technique.

Throughout history, children have often been employed in art as symbols of society. Scott’s frequent depiction of childhood in her work may be a message of warning to her audience: danger is always lurking. Alternatively, Scott may use children as they occupy a space that every viewer will recall and identify with, but continue to be mystified by. Cocteau writes of the secret world of children in his opening sequence: “the tenebrous instincts of childhood still predominate: animal, vegetable instincts, almost indefinable because they operate in regions below conscious memory, and vanish without trace, like some of childhood’s griefs; and also because children stop talking when grownups draw nigh.”[12] It is perhaps an attempt to unlock or reclaim that mystery that keeps Scott revisiting the subject.

For Les Enfants Terribles, Scott chose six scenes from the book that really stood out to her. Selected reproductions of her sketches and notes, which all together number in the hundreds, were collected into folios and accompanied the exhibition for visitors’ perusal. “I feel that for the viewer to see the working process of an artist is a wonderful way of demystifying how something ends up appearing on a wall,”[13] the artist explains. These folios, along with larger-than-life sketches painted directly onto the walls of the gallery space (Figure 2), accompanied by illustrative text from Cocteau’s book, serve as the bridge uniting image and text between the French story and the Canadian artworks. The six scenes chosen are pivotal moments in the story, and are displayed in chronological order to assist with a narrative reading. Though the artist spends countless hours sketching and mentally preparing the compositions of her canvases, “technically,” she says, “these paintings were done quite quickly,” in terms of the execution of paint applied to canvas. “They were done with white under paintings and a very specific colour ground. I tried very much to have a very specific light and mood in each piece.”[14] That light and mood is predominantly of 1930s Paris in the wintertime, lit from the exterior by yellow or blue streetlamps streaming through the window (Figure 3), and in the interior by a red scarf thrown over the lamp, casting the Room into a purplish red glow (Figure 4), creating a “womb-like enclosure.”[15] To create texture in her canvases, as an homage to the old masters and a breaking away from the flat, smooth canvases she and many other artists created during the Eighties, Scott employed an interesting technique of using pumice along with oil and acrylic paint. This creates a sturdier, more tactile surface.[16]

It is the surface of the painting that one first notices upon viewing the works. It imbues the scenes with the dreamy quality of dappled light being strewn across the characters. In “I’m still watching,” (Figure 3) the mottled effect also gives the sense of the room being haphazard and messy, but in the manner of a cosy nest. The scene that Scott is drawing from here is of Elisabeth watching over the recently injured Paul, promising her frightened young brother that she will never leave him, “except to go out for sweets or books.”[17] It is an excellent choice, as the scene marks the only instance in the story where the siblings, who obviously have a deep love for each other, actually engage in an interaction of pure and sincere tenderness. Scott’s image captures this feeling perfectly, with the children both falling asleep, and Elisabeth’s stretched out arm connecting their heads so that they may be together even in their dreams. Just ten pages prior to this scene, Gerard’s experience of Paul’s fragile state is recounted. “There had been something of perversion, almost of necrophily, in the delicious pleasures of that journey with the unconscious youth; not that he envisaged it in such crude psychopathic terms.”[18] Gerard is under the spell of the siblings, fascinated by their every movement, and ensnarled into their insular world. Elisabeth, despite all her viciousness towards him, is at heart her brother’s protector. It is only she who can truly protect Paul, as she is not under the same dumbfounded-with-admiration trance that others find themselves in. The final painting deviates significantly from the sketch paired with it in the exhibition catalogue, in setting, composition and colour scheme. The wistful, quiet mood, however, of the Room located “in the realm of phantasma, myth or dream,”[19] is consistent.

Scott had not seen Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1950 film version of the story when she started to create her images, but later described the film as perfectly capturing the mood of the book. This is not surprising, for a few reasons. Firstly, Cocteau was instrumental in the making of the film, even filming one of the scenes when the director was ill; secondly, the book is written in a cinematic manner, with few but detailed sets, and constant references to lighting,[20] thirdly, because the film’s sets and actors replicate to an uncanny degree the etchings that Cocteau made and included in his text, which is the text that Susan owns. Cocteau waited twenty years before deciding to adapt his book, because he was worried about giving the imaginary characters too concrete a form, as this might damage and interfere with readers’ own interpretations.[21] He did however, see no problem in creating two dimensional images to accompany the text, as he included many of his own etchings in one edition (Figure 5).

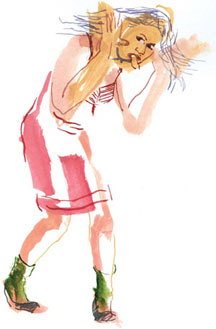

Scott’s images recall the Cocteau etchings in terms of their sketchy technique. A few of her watercolour sketches seem to be just fleshed-out versions of lost Cocteau etchings, they are so similar in style (Figure 6). Her paintings, however, are undoubtedly her own, and they function perfectly as visual representations of the text. In fact, they seem to gain a life of their own. Their connection to the text is tenuous, and not immediately apparent, as Scott takes mood as her inspiration for the images she chooses, rather than textual descriptions. In fact, sometimes they contradict the text, as in “Foul Filthy Devil,” (Figure 7) which shows Paul standing up, energetically screaming at his sister, and Elisabeth hiding her face in shame while resting on a settee. In fact, Paul was so weak that he was unable to get up from his bed, and it was Elizabeth who stood. In a documentary made about the series, Scott explains, “I took this story, but then I completely rewrote the story by choosing certain images and making scenes of certain images, and in that way losing the original context and providing a secondary context.”[22] This is by no means the first time that Scott has taken literature as inspiration, but provided additional meaning to it. Her first major work was titled “Description of a Struggle” (1983), and was based upon a short story by Franz Kafka. “I took the text from the short story and I rewrote that short story to make it my own,”[23] says Scott of this first piece, her delivery authoritative and matter-of-fact, as if it never crossed her mind that there could be an issue with appropriating without consent the fruits of someone else’s labour.

In his landmark essay, “The Death of the Author” (1977), Roland Barthes criticizes the tradition of analysing works of art or literature primarily according to the biography of their architect. Barthes believes that “to give a text an author is to impose a limit on that text,”[24] and that “to give writing its future, it is necessary to overthrow the myth: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.”[25] The author is a modern invention, he asserts, stating that “in ethnographic societies the responsibility for a narrative is never assumed by a person but by a mediator, shaman, or relator whose ‘performance’ – the mastery of the narrative code – may possibly be admired but never his ‘genius.’”[26] It is likely that Scott, an avid reader, agrees. She is a lover of stories, and her work shows plainly that she considers her obligation to her artistic desire to create images paramount, regardless of the degree of fidelity to the text from which she drew her inspiration. All things considered, the Les Enfants Terribles series is much more so about Scott’s artistic process than it is about any French novel from the 1930s, any troubled children, or any drug-addicted poet. Her exhibition was a grand act of dethroning the Author and heralding the triumph of the reader-artist. The bombardment of images present at the exhibition – the piles of sketches, the large sketches filling the spaces between the canvases, even a wall painted red to enhance the colours in “The Red Room” – all serve to crowd out Cocteau. The only direct references to the author were the brief passages inscribed upon the walls, which were actually taken out of context and ascribed new meaning as Scott saw fit.

“I’ve always wanted my paintings to be accessible,” says Susan. “All along, I’ve always tried to choose stories, narratives to create paintings around, where the viewer felt like they could participate in that story, they could relate to that story, they could put themselves in the story, and whether or not you understand the source of the narrative, it doesn’t really matter, because the paintings end up having a life of their own, I hope.”[27] Taking a loving departure from the details of Cocteau’s visionary work, Scott fashions her own private world amongst the mythical characters. “They felt the tug of the current carrying them towards night, towards renewal, life, the Room,” writes Cocteau of his feral orphans in reference to their den. He is unaware that he is providing an artist with the perfect metaphor for the creative impulse. In Les Enfants Terribles (A Painter’s Narrative), Susan G. Scott is inviting the public to enter the sacred space of her Room: her creative mind. It is, like the children’s room, filled with treasure.

Bibliography

“Susan G. Scott” Shaping Art #7, DVD, Shaping Art Documentary Series (BRAVO TV), 2004.

Baron Turk, Edward, “The Film Adaptation of Cocteau’s “Les Enfants terrible””, Cinema

Journal Vol. 19, No. 2 (Spring, 1980), pp. 25-40.

Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author,” Contemporary Literary Theory Electronic Reserve.

http://social.chass.ncsu.edu/wyrick/debclass/whatis.htm by Dr. Deborah Wyrick, Last updated January 2003. Accessed November 2008.

Bordo, John, “Translation: Narrative into Painting, Susan G. Scott after Cocteau,” Susan G.

Scott, “Les Enfants Terribles (A Painter’s Narrative)” Exhibition catalogue, Galerie McClure/Centre des Arts Visuels, pp. 2-7

Cocteau, Jean, Les Enfants Terribles/The Holy Terrors, Translated by Rosamond Lehmann., Norfolk, Connecticut: New Directions Books, 1957.

McNab, James P., “Mythical Space in Les Enfants terrible”, The French Review. Special Issue

No. 6, Studies on the French Novel (Spring, 1974), pp. 162-170

Read, Peter, “Review: [Les enfants terribles]”, The Modern Language Review Vol. 84, No. 1 (Jan., 1989), pp. 186-187

Scott, Susan G., Excerpt from notebook. Sketchbook Folio #4. 2004., p. 1

Images

Cocteau, Jean, Les Enfants Terribles/The Holy Terrors, Translated by Rosamond Lehmann., Norfolk, Connecticut: New Directions Books, 1957.

Scott, Susan G., Painting Series. www.susangscott.com. (Accessed November 3, 2008).

Scott, Susan G. Paintings from Susan G. Scott, “Les Enfants Terribles (A Painter’s Narrative)”

Exhibition catalogue, Galerie McClure/Centre des Arts Visuels. All photographs of catalogue pages by author.