NOTATIONS

“It has always been a happy thought to me that the creek runs on all night, new every minute, whether I wish it or know it or care, as a closed book on a shelf continues to whisper to itself its own inexhaustible tale. So many things have been shown so to me on these banks, so much light has illumined me by reflection here where the water comes down, that I can hardly believe that this grace never flags, that the pouring from ever-renewable sources is endless, impartial, and free.”

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

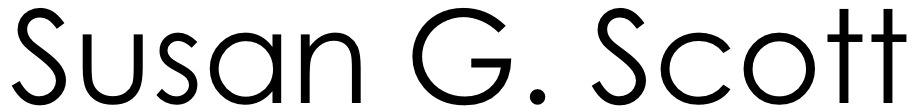

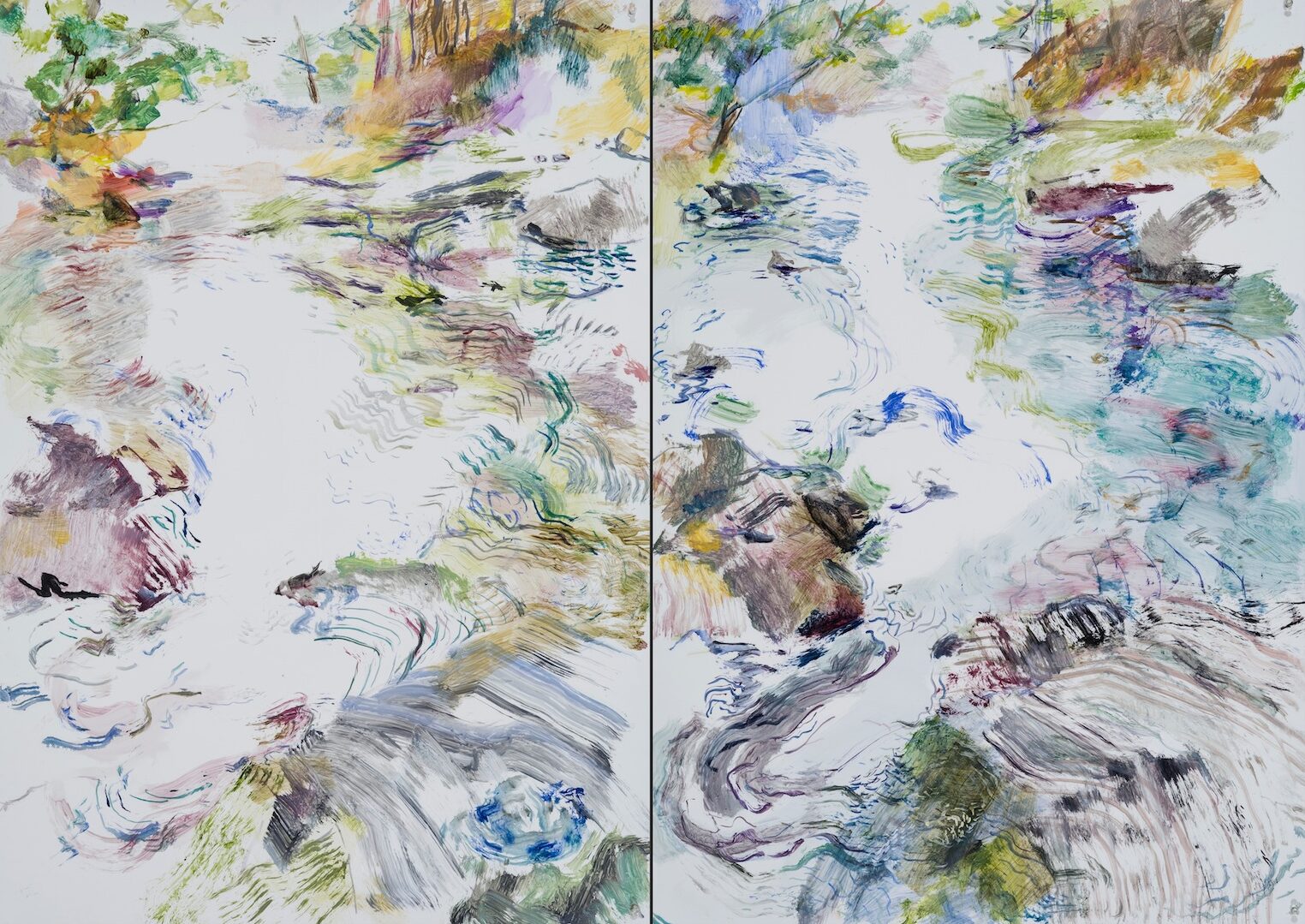

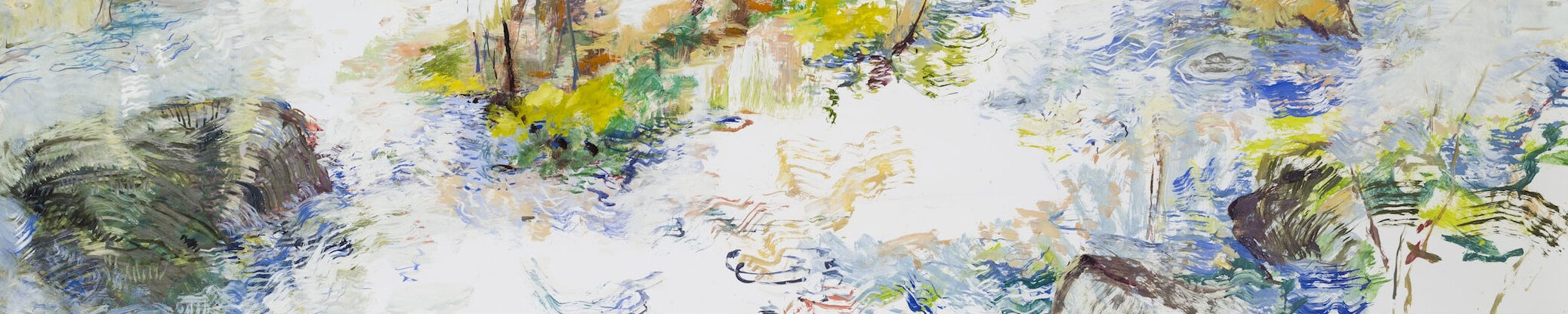

There is an exhilarating sense of freedom and surprise in Susan Scott’s recent paintings. Brushstrokes tumble over each other in turbulent and ecstatic

trajectories. The slick, white grounds of the terra skins reveal the minutiae of mark- making in a bold and unforgiving way like the precision of a child’s fingerprint on the side of a refrigerator. Scott tells me that she has been buying brushes at the hardware store, trimming them herself so that their bristles can more easily translate the energy of the water, rocks and fir trees of the Vermont creek that flows through the forest near her summer studio. Like all artists in the midst of a change, she is nervous. Amazed that she is doing purelandscapes. Worried about the absence of the figure.

Good paintings demand that you look at them intently, savoring and measuring every inch like a pleasure seeking detective. It’s easy to do this with the Notations series, following the moods of light and colour, the shifts in paint handling from dry scumbles, to juicier licks that drag, then flow, then skip across the picture plane. Everything in concert with the creek, its jittery path turned into pigment, gesture and sometimes fracture. The smallest touches are hatch marks providing form and direction but also breaking the image down to the microscopic, to water droplets, dust, air and insects. It’s interesting that Susan has chosen the creek as a motif. Obviously the physical circumstances of her studio played a part, but I can’t help but feel that she has found a match for her own restless energies. The rushing tributary, a perfect foil for her own nervous system.

In a broader context, Susan’s new paintings belong to Western culture’s rather knotty relationship with nature. From Constable’s clouds to Monet’s water lilies, to Sargent’s Venetian watercolours, to Tom Thomson’s oil sketches of Algonquin Park, capturing the world’s fleeting moments in a few deft strokes of paint was one of the driving forces of modernist painting. And yet there are few signs of that legacy now. Whatever happened to Naturalism anyway? Sure everybody loves the Impressionists and other painterly painters of the late 19th century (Barbizon School, Corot, et al) and yet the general feeling is that such an approach belongs to that particular time and place. It has become passé in an era geared to various conceptualisms and internalizations, an era in which our relationship to nature is just something else that has become mediated. Landscape continues with Sunday painters, although that has always been formulaic and superficial and one suspects that even they generally bypass working en plein air, offering the natural world as something demure and domesticated. It seems to me that one of the last great painters to capture nature in all of its unbridled glory was the abstractionist Joan Mitchell and I confess I find myself thinking about her

in the presence of Notations. Who knows whether Scott will remain on this road or

where it will lead her, but for now these new paintings are a source of tremendous energy and promise.

DAVID ELLIOT

David Elliott, Professor, Department of Studio Arts at Concordia University in Montréal, is a painter who also writes about art. His book-length essay, imagination “The Radical Theatre of Alfred Leslie,” was published in New York in 2007 by Ameringer/Yohe.